The Koh-i-Noor diamond has had a bloody history, passing through the hands of various rulers and empires over the centuries before becoming part of England’s Crown Jewels.

Public DomainA 1919 depiction of Queen Mary’s crown. The Koh-i-Noor diamond sits at its front.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond is one of the most famous gemstones in the world. Although its precise origins are a mystery, most scholars believe it was mined in India between 1100 and 1300 C.E.

Since then, the diamond has passed through the hands of countless emperors and kings through violent means. As it moved through the Mughal Empire, the Persian Empire, and then the Sikh, it left a long trail of bloodshed in its wake — leading to rumors that the diamond may be cursed.

After triumphing over the Sikh Empire in the 19th century, the British Empire secured the Koh-i-Noor diamond for itself. The diamond has remained an integral part of the Royal Crown Jewels ever since. And despite several demands from countries like India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan to return the Koh-i-Noor, the United Kingdom remains steadfast in its decision to keep the priceless diamond.

The Murky Origins Of The Koh-i-Noor Diamond

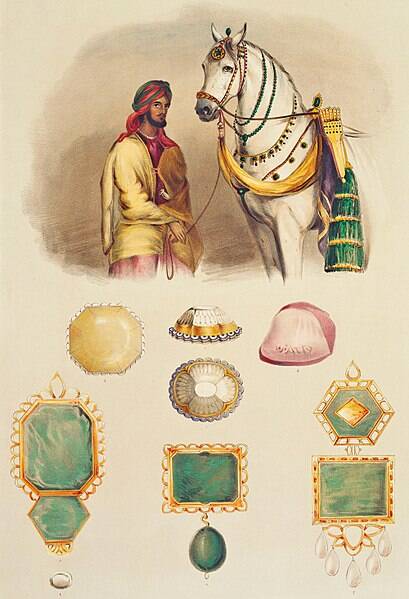

Public DomainAn 1844 lithograph showing Maharaja Ranjit Singh with his treasure, including the Koh-i-Noor at top center.

The history of the Koh-i-Noor is something of a mystery. Believed to have originated in the Golconda mines of India, the gemstone has likely circulated through the hands of royals and aristocrats for at least 700 years.

Originally, the Koh-i-Noor diamond was an astonishing 186 carats, making it one of the world’s largest cut diamonds. According to The Guardian, an 18th-century Afghan queen named Wufa Begum once tried to articulate the gem’s worth: “If a strong man were to throw four stones, one north, one south, one east, one west, and a fifth stone up into the air, and if the space between them were to be filled with gold, all would not equal the value of the Koh-i-Noor.”

Based on a number of written records, the Mughal Empire acquired the stone sometime during their reign over India, between the 16th to the mid-17th century. Then, in 1628, the Mughal ruler Shah Jahan commissioned the Peacock Throne, an ornate imperial seat encrusted with hundreds of jewels. And set at the very top of the throne was a massive diamond.

In 1739, Emperor Nader Shah of Persia’s Afsharid dynasty invaded India, slaughtering thousands, capturing Delhi, and raiding the Mughal Empire’s treasury. When he first saw the Mughal emperor’s prized diamond, Nader Shah reportedly exclaimed “Koh-i-Noor!” — the Persian phrase meaning “Mountain of Light.” The diamond has been called Koh-i-Noor ever since (also spelled Koh-e-Noor, Kohinoor, and Koh-i-Nur).

Unfortunately for Nader Shah, he was assassinated only a few years later. The Koh-i-Noor fell into the hands of his general, Ahmad Shah, and for several decades it passed from ruler to conquering ruler in present-day Afghanistan.

But by the early 19th century, the Koh-i-Noor had fallen into the hands of Ranjit Singh, founder of the Sikh Empire. Finally, the diamond was back in India.

But it wouldn’t remain there for long.

The British Empire Takes Possession Of The Diamond

Public DomainQueen Victoria depicted in a 1856 portrait wearing the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh fell ill and died on June 27, 1839. Afterward, a bloody battle for succession ensued. The Koh-i-Noor diamond passed through multiple hands with each shift in power until the Sikh finally installed a new Maharaja in 1843: Ranjit Singh’s son, five-year-old Duleep Singh. The young emperor wore the diamond on his arm as his father before him had done.

The Koh-i-Noor remained there until the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War, a military conflict between the British East India Company and the Sikh Empire. In 1849, the British annexed the Kingdom of Punjab, imprisoned Duleep’s mother, and made the Maharaja, then only 10 years old, sign the Last Treaty of Lahore, which ceded both his kingdom and the Koh-i-Noor to the British Crown.

For the British, owning the Koh-i-Noor was a symbol of power and control over India. When they had first heard of Ranjit Singh’s death, they became determined to claim not only India, but its beloved jewel as well. The East India Company started keeping close tabs on the whereabouts of the diamond, and it ultimately paid off.

In July 1850, the Koh-i-Noor arrived at Buckingham Palace. It went on display in London during the Great Exhibition of 1851, where it was a star attraction.

Then, in 1852, royal officials had the diamond recut to remove “imperfections” — taking it from 186 carats to its current weight of 105.6 carats. It was then fashioned into a brooch for Queen Victoria.

Following her death in 1901, the Koh-i-Noor was added to the crown of Queen Alexandra, and in the subsequent years, it was added to the crowns of Queen Mary in 1911, and Elizabeth the Queen Mother in 1937.

AF Fotografie / Alamy Stock PhotoQueen Alexandra wearing the Koh-i-Noor diamond during the coronation of King Edward VII in 1902.

During World War II, the royal family removed the Koh-i-Noor and the other Crown Jewels from the Tower of London and buried them in a cookie tin 60 feet beneath Windsor Castle to protect them from Nazi invasion. The Koh-i-Noor was returned to the Tower of London after the war ended, and has remained a prized part of the royal Crown Jewels ever since.

The Koh-i-Noor made its last public appearance at the funeral of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother in 2002. The diamond shone on the late Queen’s crown, which sat on top of her coffin during the ceremony.

The Controversy Surrounding The Koh-i-Noor’s Provenance

Today, many view the Koh-i-Noor as a symbol of conquest and a token of colonial violence. Since India regained its independence in 1947, the country has called upon Britain to return the Koh-i-Noor several times. And it’s not the only country to lay claim over the diamond. Pakistan likewise asked for its return in 1976, and Afghanistan made a similar demand in 2000.

The British government has denied these demands each time, claiming that the diamond was given to them legally. And some experts have also stated that part of the reason the Koh-i-Noor hasn’t been returned to its rightful owners is that it’s difficult to determine just who has the most legitimate claim over the diamond.

“You’re dealing with countries that existed when the object was acquired, but they may not exist now — and countries which we had trade agreements with that may have different export laws now,” Jane Milosch, the director of Smithsonian’s Provenance Research Initiative, told Smithsonian in 2017.

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock PhotoGeorge VI of Great Britain at his coronation in 1937. His wife, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, wears the Koh-i-Noor diamond on her crown.

“Provenance is very complex and people aren’t used to processing a chain of ownership. By the time you hit the second or third owner over time, the information can get more difficult to research,” Milosch added. “This is why I say it’s important that these things not be yanked out of museums, because at least people have access and can study them until we know for sure if they were looted.”

For others, the matter is fairly simple. They believe that Britain should return the diamond to its country of origin — or at the very least, create a plaque explaining the truth of how it wound up in British hands.

“If you ask anybody what should happen to Jewish art stolen by the Nazis, everyone would say of course they’ve got to be given back to their owners,” William Dalrymple, a historian and author, told Smithsonian. “And yet we’ve come to not say the same thing about Indian loot taken hundreds of years earlier, also at the point of a gun. What is the moral distinction between stuff taken by force in colonial times?”

“What I would dearly love is for there to be a really clear sign by the exhibit,” Dalrymple added. “People are taught this was a gift from India to Britain. I would like the correct history to be put by the diamond.”

As of today, the British Royal Family has no known intention of returning the Koh-i-Noor to India or any other country. Only time will tell if increasing international pressure will bring the Koh-i-Noor back to its birthplace.