Shi Pei Pu was a male opera singer and spy who convinced his lover, French diplomat Bernard Boursicot, that he was a woman for nearly 20 years before they were both found guilty of espionage.

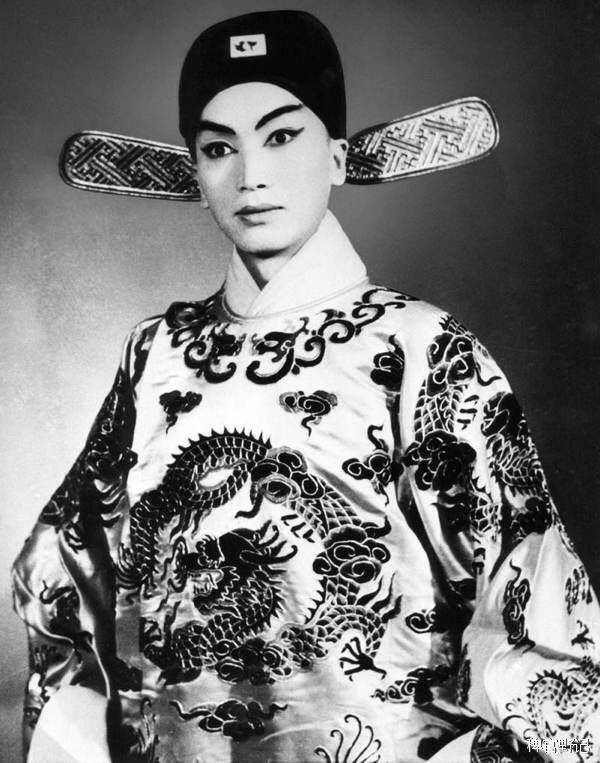

Public DomainAs a young opera singer, Shi Pei Pu enjoyed modest fame in Beijing and often played female roles.

In 1964, Bernard Boursicot, an employee of the French embassy in Beijing, met a beautiful opera singer named Shi Pei Pu at a Christmas party. The two immediately hit it off, and soon embarked on a secret 18-year-long love affair.

But under Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, Chinese people were forbidden to mix with foreigners, and eventually, Boursicot agreed to trade embassy secrets to the Chinese government in order to continue seeing Shi.

In 1983, the French government arrested the pair for espionage. It was only then that the truth finally emerged: Shi was not a woman, as Shi had told Boursicot for the duration of the affair.

During their trial, Shi identified himself as a man. For nearly 20 years, he explained, he had convinced Boursicot that he was a woman by hiding his genitals and insisting on having sex only in the dark. He even secretly adopted a child to present as their biological son.

Shi and Boursicot were both convicted of espionage by the French government. In the years that followed, Shi insisted that their love had been real. But when Shi died in 2009, an embittered Boursicot reflected on their relationship, telling The New York Times, “He did so many things against me that he had no pity for; I think it is stupid to play another game now and say I am sad. The plate is clean now. I am free.”

This is the story of Shi Pei Pu, the Chinese opera singer accused of posing as a woman to extract secrets from a French diplomat.

How The Relationship Between Shi Pei Pu And Bernard Boursicot Began

Shi Pei Pu was born in 1938 in the coastal Chinese province of Shandong. According to The New York Times, Shi learned French while growing up in the city of Kunming, which has a strong French influence. He attended Yunnan University, majoring in literature. By the age of 17, he had gained local recognition as an opera singer, often playing female roles.

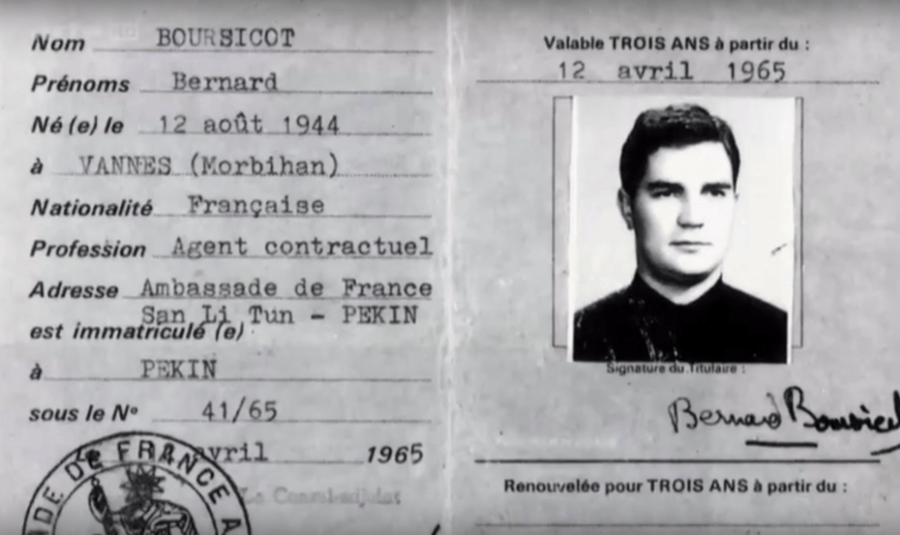

Bernard Boursicot was born in France in 1944. Throughout his youth, he attended boarding schools, where he had same-sex relationships with several fellow students. But by the time he arrived in Beijing at the age of 20, he was seeking a relationship with a woman, believing his relations with men were just a “schoolboy’s game.”

YouTubeBernard Boursicot worked for the French embassy in Beijing as an accountant.

In 1964, while stationed at the French embassy in Beijing, Boursicot was invited to a Christmas party hosted by Claude Chayet, the second-highest official at the embassy. The party was for French students, but there was a short, thin Chinese man there who caught Boursicot’s eye. The two struck up a conversation, and the man told Boursicot his name was Shi Pei Pu and that he taught Chinese to the Chayet children’s tutor.

Shi and Boursicot soon became close friends, telling each other things they’d never felt comfortable sharing with anyone else. Then, Shi revealed a secret that would forever change the nature of their relationship.

The Tale Of The Butterfly Lovers

At first, Boursicot and Shi’s relationship was strictly platonic, as Boursicot was still determined to find a female partner. Then, Shi told him a tale called “The Story of the Butterfly” about a schoolgirl in ancient China named Zhu who dresses as a boy so she can attend school.

While in school, Zhu falls in love with a schoolboy named Liang, who in turn is confused about his attraction to a fellow boy. Eventually, Zhu’s family sends for her to return home, telling her they’ve found her a husband. Before Zhu leaves, she finally reveals her true identity to Liang, and they profess their love for each other. Liang asks Zhu to marry him, but she tells him it’s too late.

Liang is so heartbroken to lose Zhu that he takes his own life, and Zhu, distraught over the death of her true love, visits Liang’s grave — and throws herself inside it to join him. The lovers’ spirits take the form of butterflies, and they fly away, free to be together at last.

After Shi told Boursicot this story, Shi held up his small hands and told him, “Look at my hands. Look at my face. That story of the butterfly — it is my story, too.”

Shi explained that his paternal grandmother had given his mother a decree: If she did not give the family a son, Shi’s father would have to take a second wife. When Shi was born, they realized the baby was a girl. Not wanting to lose her place in the household, Shi’s mother and the midwife made a pact to raise the baby as a boy and keep the real identity secret from Shi’s grandmother. Shi had been living as a man ever since.

Realizing that Shi was a woman, Boursicot suddenly saw her in a whole new light — and realized they could now pursue a romantic and sexual relationship.

At first, their romance was strained and cold. Whenever they had sex, it was always hurried, under cover of darkness. Meanwhile, Shi continued to dress and live as a man publicly. It was only ever with Boursicot that she lived as a woman.

Eventually, Boursicot’s assignment came to an end. Shortly before Boursicot left China in the winter of 1965, Shi told him she believed she was pregnant.

“I will be back,” he told her. “For sure. I don’t know how. Just remember I will be back.”

Bernard Boursicot Begins Trading Secrets To The Chinese Government

Four years later, Bernard Boursicot kept his promise. He returned to Beijing, this time as an archivist for the embassy. But he had come back to a very different Beijing. Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution had begun, and Chinese citizens were not allowed to mix with foreigners without the approval of the Chinese government

Still, bent on finding his lover and, possibly, his child, Boursicot wrote to Shi Pei Pu the very first day he got back, and spent days searching for her.

When he finally found her, she told him that she had given birth to his son the summer after he left. But she explained that, because the boy was half-European, she’d had to send him to live with family near the border of Russia out of fear for his safety.

Boursicot would not meet his son for years. During that time, at great risk to his own safety, he continued to visit Shi under the guise that she was teaching him about the Cultural Revolution.

One day, Shi told Boursicot that a Beijing city government representative would be taking over as Boursicot’s teacher. A man named Kang soon showed up at Shi’s house while Boursicot was visiting. Sensing that Kang was a police officer, Boursicot offered the Chinese government something in exchange for continuing his relationship with Shi.

“How can I help the people?” Boursicot asked Kang. “If, for example, we had news at the embassy…”

Thus began Boursicot’s work as a spy for the Chinese government. He regularly gave Chinese officials reports from the French embassies in Moscow and Washington, and his relationship with Shi was allowed to continue.

Shi later claimed to not have any knowledge of Boursicot’s espionage.

“I was unaware that my friend Bernard Boursicot had given documents to the Chinese authorities and most particularly to an individual named Kang whom he would meet at my home in Beijing outside of my presence and without me knowing about it,” Shi said.

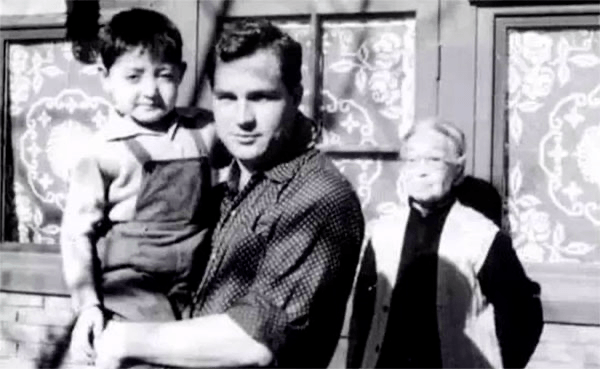

In 1973, Boursicot was finally allowed to meet his son, Shi Du Du, who was now seven years old. Shi claimed that because the country was becoming more liberal, it was finally safe to bring the boy home. For a few blissful weeks, they were able to together as a family. Then, Boursicot’s visa ran out, and he was forced to return to France.

YouTubeBernard Boursicot is pictured here with Shi Du Du, who he believed was his biological son. It turned out his son was adopted from China’s Xinjiang province.

The Arrest Of Bernard Boursicot And Shi Pei Pu

Bernard Boursicot quit his job as a diplomat and moved back to Paris, where he started a relationship with a man named Thierry.

But he soon became restless, and he wanted to see Shi and their son. He asked Thierry if he could bring Shi and Shi Du Du to live with them in Paris. Thierry reluctantly agreed.

Shi and Shi Du Du arrived in 1982, and moved in with Boursicot and Thierry. Shi quickly built a new opera career for herself, though she still maintained her male identity in public, realizing that she may need to return to China at some point.

However, all of the romance between Shi and Boursicot was gone. Boursicot now saw their relationship as one of duty, or obligation. But they continued to live together in Paris for the next year — until 1983, when both they were both arrested for espionage.

Late in 1982, the French government had been conducting what they claimed was normal surveillance of Chinese diplomats in Paris when they discovered something interesting: “the relationship between Bernard Boursicot, identified in their files as ‘a civil servant at the Ministry of Exterior Relations posted abroad,’ and ‘a Chinese national… later identified as Shi Pei Pu who is living at Boursicot’s address.”

In June 1983, French security agents arrested Boursicot and charged him with espionage. A week later, they arrested Shi.

That was when Shi’s lies began to unravel.

The Truth About Shi Pei Pu Is Revealed

Olivier Boitet/Associated PressBernard Boursicot (left) and Shi Pei Pu were both convicted of espionage in France and sentenced to six years in prison.

An investigation soon revealed that Shi Pei Pu’s story about being born a girl and being forced by her parents to live as a boy was patently false. In prison, medical examinations showed Shi had intact male genitalia. Shi demonstrated to doctors how he was able to hide his genitals during sex to convince Boursicot he was a woman.

Later, Shi testified in court that he was a man.

“I never told Bernard I was a woman,” Shi said to the judge. “I only let it be understood that I could be a woman.”

But this raised another question. How had Shi given birth to Boursicot’s son?

At first, Shi claimed that Shi Du Du was indeed Boursicot’s biological son, but had been conceived through the use of artificial insemination. But as it turned out, Shi had adopted Shi Du Du when he was four years old. As reported by the Telegraph, Shi Du Du’s mother had sold him, as their family was part of the Uyghur ethnic group, which was being oppressed and impoverished in China.

Distraught over the lies he had been told for nearly 20 years, Boursicot attempted suicide in his prison cell while awaiting trial. Thankfully, he survived. But he never quite forgave Shi Pei Pu.

The Aftermath Of The International Scandal

Both Shi Pei Pu and Bernard Boursicot were convicted of espionage and sentenced to six years in prison. But less than one year later, Shi received a presidential pardon. Reportedly, the French government did not want to endanger relations with China over a “very silly” case. Boursicot received a pardon a few months later.

During the trail, the case of Shi Pei Pu and Bernard Boursicot had sparked a media frenzy, and people around the world became fascinated by this tale of forbidden love and espionage. The story even inspired the 1988 Tony Award-winning play M. Butterfly, which in turn was adapted into a movie by the same title in 1993.

After being released from prison, Shi remained in Paris with Shi Du Du and continued to use male pronouns. Although Boursicot and Shi exchanged contact a few times over the years, it was always strained. While Shi claimed to still love Boursicot, Boursicot harbored resentment toward his former lover.

Shi Pei Pu died in 2009 at the age of 70. In recent years, some have speculated that Shi may have been a transgender woman, and that it was perhaps a lack of terminology or fear of violent repercussions that prevented Shi from living freely as a woman. In any case, it appears Shi had a fluid approach to gender.

“I used to fascinate both men and women,” Shi said in an 1988 interview. “What I was and what they were didn’t matter.”