Joe Gallo paraded his pet lion around New York, kidnapped his own bosses, and sparked two gang wars before he was finally gunned down in Little Italy in 1972.

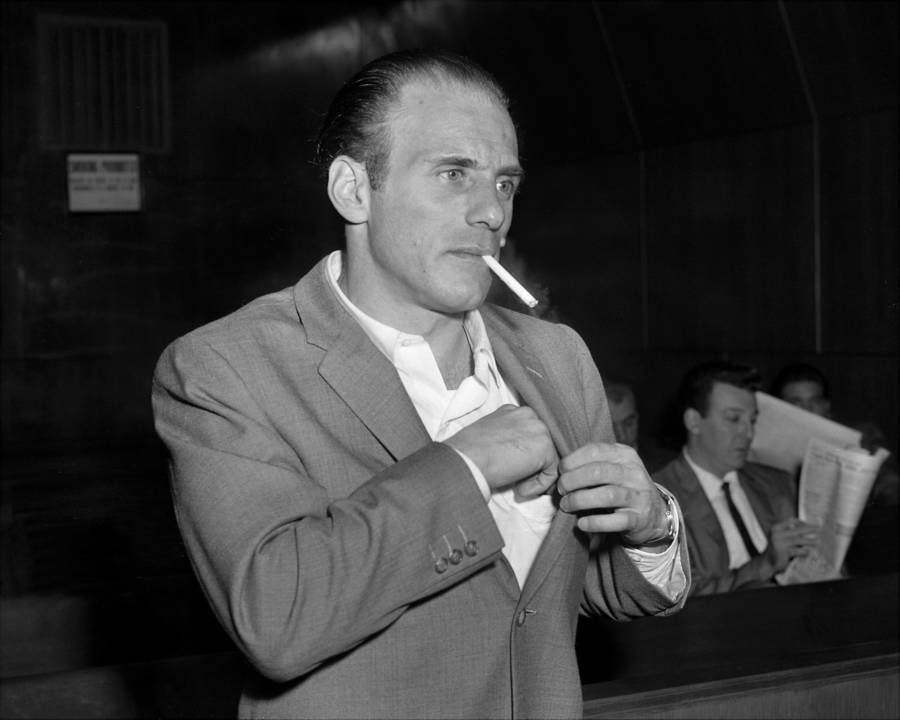

New York Daily News Archive/Getty Images“Crazy” Joe Gallo kidnapped the bosses of his own family in a bid to gain a higher cut of profits.

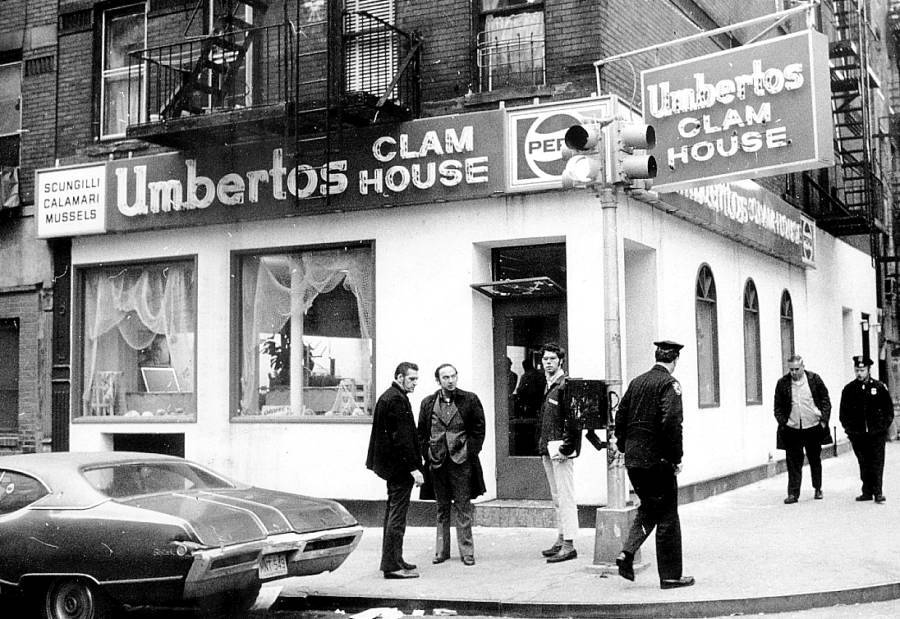

On April 7, 1972, infamous mobster Joe Gallo sat down to celebrate his birthday at Umberto’s Clam House in New York’s Little Italy with his family. As they ate, a group of men rushed into the room, guns in hand. The men began to fire as Gallo stood up and pulled out his own gun to fire back.

Gallo knocked over a table to provide some cover from the bullets flying through the air and began moving towards the door, likely hoping to draw the fire away from his family.

The bullets hit him, but he managed to stumble into the street, where he finally collapsed. As the gunmen fled, the police raced to the scene and found the mortally wounded Gallo. At the funeral three days later, his sister declared, “The streets are going to run red with blood, Joey.”

As it happened, she was right. “Crazy” Joe Gallo had lived by the sword — starting a war against his Mafia bosses for control of the family — and in the end, he died by the sword, as well. This is the unpredictable, blood-soaked story of Joe Gallo.

A Life Of Murder And Mayhem

Born in Brooklyn to a father who had been a bootlegger during Prohibition, Gallo quickly followed his old man into a life of crime. He grew up in Kensington, where his family operated a “greasy spoon,” a small, cheap restaurant that typically served fried foods.

Joe Gallo eventually dropped out of high school at 16, and shortly after he was involved in an automobile accident that caused him to develop a “nervous tic.” Around this time, he and his friends, “Pete the Greek” Diapoulas and Frank Illiano, formed a small gang and began planning various criminal schemes.

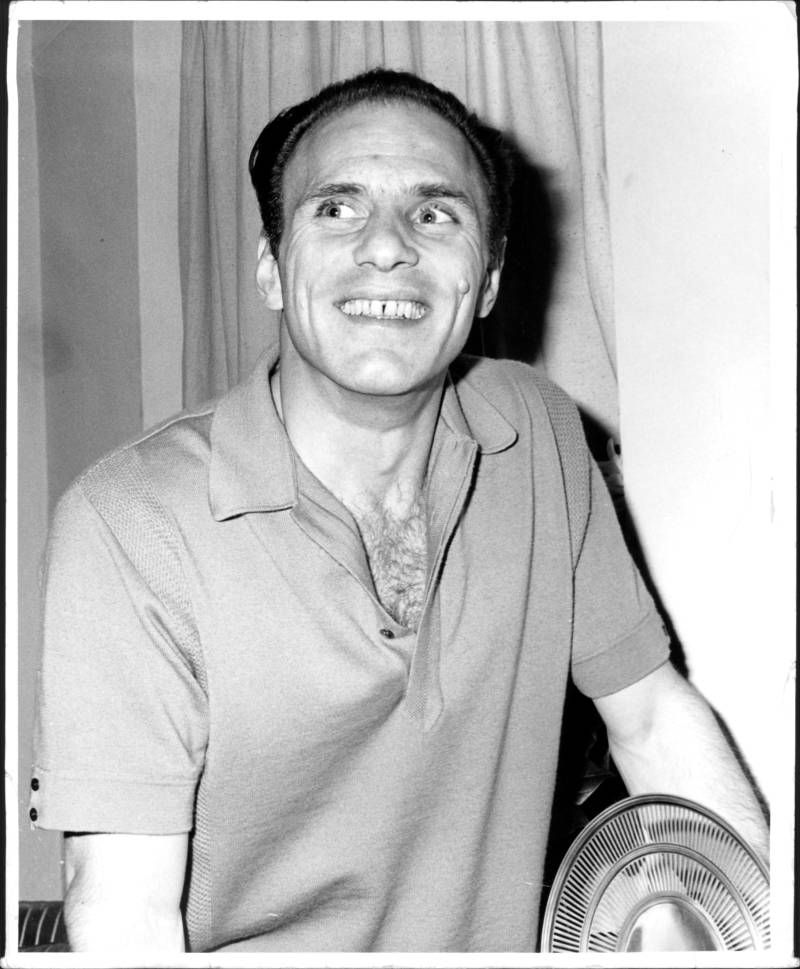

colaimages / Alamy Stock PhotoJoe Gallo formed his own crew with his brothers Larry and Albert.

He later fell in with local Mafia associates who nicknamed him “Joey the Blond.”

It was somewhat poetic, too, as Gallo had become infatuated with movies about criminals, particularly 1947’s Kiss of Death. He would often quote Richard Widmark’s gangster character, Tommy Udo, and he even began speaking like him.

After an arrest in 1950, Gallo was evaluated by doctors, who diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia. Over the next few years, Gallo earned another nickname: “Crazy Joe.”

Gallo got his start stealing jukeboxes and candy machines and reselling them. He was soon a “jukebox racketeer,” using violence to ensure that anyone in the area who wanted one had to buy it from him. And often, so did people who didn’t. When one business owner decided he didn’t want to buy a machine, Gallo reportedly whipped out a knife and held it to his throat until the man changed his mind.

Eventually, Gallo was so notorious that in 1958 he was called into the office of Senator Bobby Kennedy during congressional hearings on organized crime. “Nice carpet,” Gallo said after walking into the room, as reported by the New York Daily News. “Good for a crap game.”

Joe Gallo joined the Profaci family early on, serving as the most likely hitman of Albert Anastasia, the boss of what would become the Gambino family.

As the head of Murder Inc. — the Mafia’s most notorious hit squad — Anastasia was one of the most feared men in New York. While most people would have wanted to keep the fact that they’d murdered a Mafia boss quiet, Gallo later bragged publicly about gunning Anastasia down in a barber’s chair alongside his brothers, Larry and Albert, and Carmine Persico.

“You can just call us the barbershop quartet,” he said.

‘Crazy Joe’ Takes On His Own Bosses And Starts A War

Joe Gallo expected a hefty reward for his part in the killing of Anastasia. When Joe Profaci, head of the family, failed to give it to him, Gallo quietly began planning to take over his rackets for himself. Hearing what Gallo was planning, Profaci authorized a hit.

While most men with their sanity intact might take the opportunity to skip town, Gallo struck back recklessly. He kidnapped one of Profaci’s brothers, Frank, and held him hostage, along with three of Profaci’s top men: Joseph Magliocco, Salvatore Musacchia, and John Scimone.

Joe Profaci, meanwhile, managed to avoid being captured and fled to Florida to seek sanctuary.

What followed was a string of murders as the two factions went to war. The Gallos and Profaci eventually reached an agreement for the peaceful release of the hostages — which Profaci was quick to break, attempting hits on both Joe Gallo’s brother Larry and another gang member, Joseph Gioielli.

Larry Gallo survived, but the attempt reignited the gang war.

Unfortunately for “Crazy Joe,” he was arrested for conspiracy and extortion in 1961 before he could see how the war played out, landing him a sentence of seven to 14 years in prison.

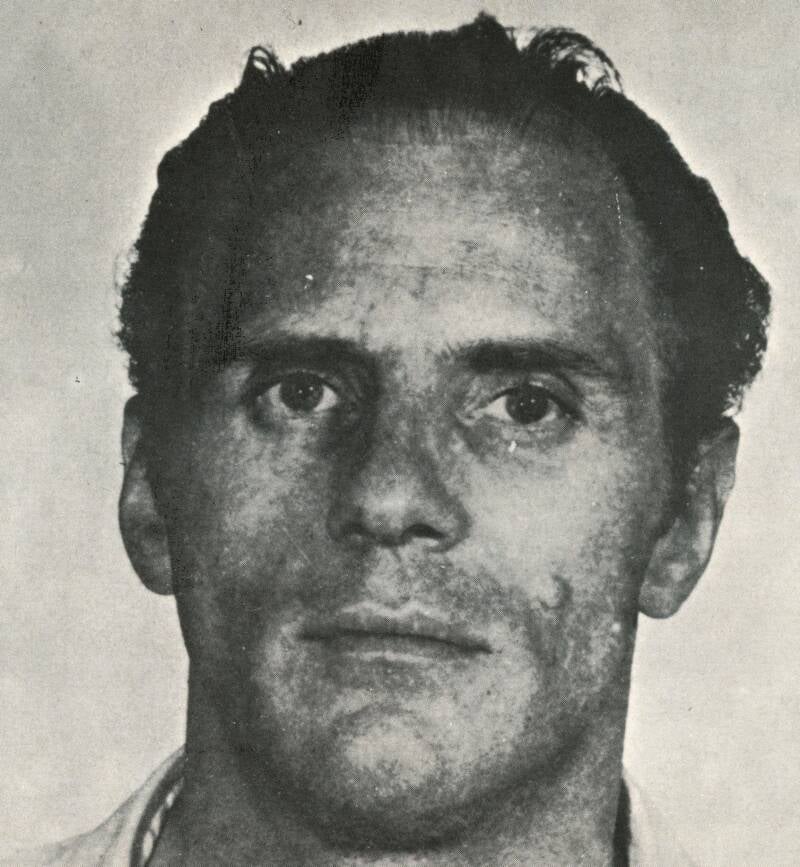

Getty ImagesTensions within the Colombo family died down while Joey Gallo was in prison, but immediately upon his release, the war began anew.

While he was behind bars, Joe Gallo went through a sort of reinvention, taking up painting and studying literature and philosophy. Unusually for men in the Mafia, Gallo struck up friendships with Black prisoners while he was inside. These connections would eventually prove useful for operating in Black neighborhoods when he was released.

The Final Clash With The Colombos And The Death Of ‘Crazy’ Joe Gallo

Word began circulating that Gallo planned to use his new friends to finish his war against the Profaci family, now under the control of mobster Joseph Colombo.

In June 1971, Colombo was shot by a gunman pretending to be holding a camera. The boss survived the shooting but was paralyzed for the rest of his life. Colombo’s associates noted that the gunman was Black, and fingers were quickly pointed at Gallo.

“Crazy” Joe Gallo wasn’t particularly concerned. In spite of the fact that one of the largest crime families in New York wanted him dead, Gallo took no real precautions for his safety. So when a Colombo associate spotted him in a Little Italy restaurant, it was easy for him to return with backup and gun Gallo down.

New York Daily News Archive/Getty ImagesThe scene of Joe Gallo’s death at Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy on April 7, 1972.

However, Frank Sheeran, an enforcer for the Bufalino crime family, later claimed responsibility for Gallo’s assassination, saying he was ordered to take him out because his flashy lifestyle was drawing attention to the Mob. Still, there is no evidence that he was actually involved.

Gallo’s death set off another war between Gallo’s crew and the Colombo family. At least 10 men were killed in the series of gangland slayings that followed.

The war lasted several years before the rest of Gallo’s family was able to make peace and rejoin the Colombo family. It was the most violent Mafia war in New York in decades.

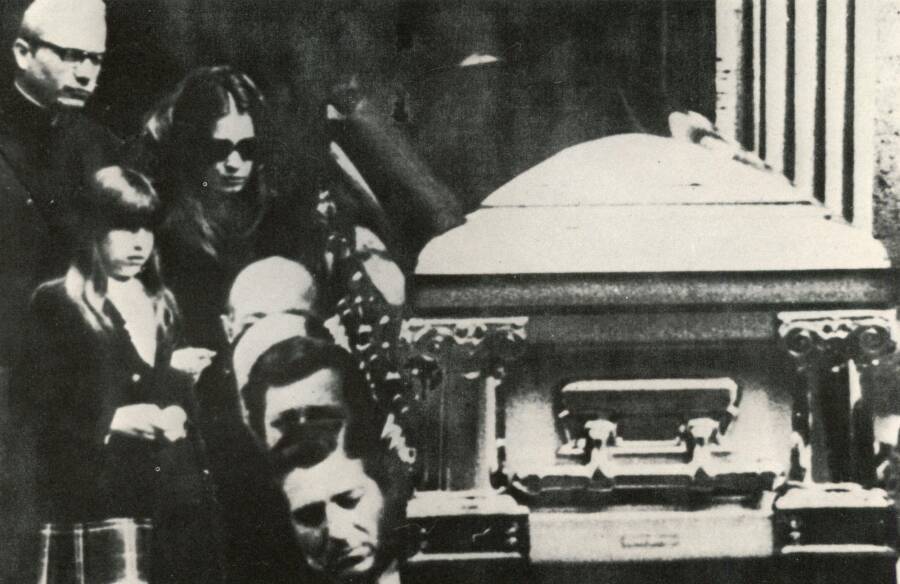

colaimages / Alamy Stock PhotoJoe Gallo’s funeral.

Before his death, Joe Gallo had been cultivating an image as a folk hero, associating with the art scene in New York. Bob Dylan even wrote a song about him called “Joey.”

“I never considered him a gangster,” said Dylan. “I always considered him some kind of hero… An underdog fighting against the elements.”