The Sahara was once a grassy woodland until human activity and a changing climate turned it into the immense desert we know today. The Berbers were the only people who decided to call it home.

he men who belong to this family of peoples,” the eighth century Tunisian historian Ibn Khaldun remarked of the Berbers, “have inhabited the Maghreb since the beginning.”

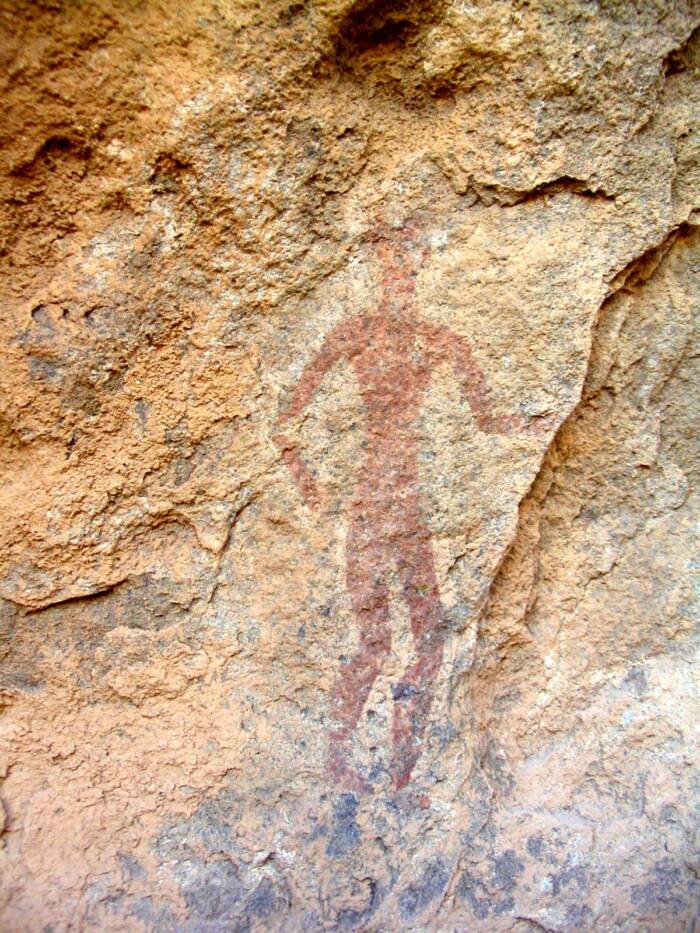

Indeed, the Berbers — also known as the Imazighen, or “free men” — have lived in North Africa since the beginning of recorded human history. Evidence of their existence in the region, known as the Maghreb, dates back to at least 10,000 B.C.E. in the form of cave paintings and rock art.

They were the original inhabitants of this corner of the world. When the Romans, Greeks, Carthaginians, and later the Arabs, arrived in the region, it was the Berbers that they first encountered. But while many of these empires fell, the Berbers endured. Over the millenium, they spread west across northern Africa, establishing strongholds in the present-day countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mali, Niger, and Mauritania.

Many are still there to this day. But as the world has changed, the Berbers have too. They’ve adapted to new religions, new world powers, and new technologies. And in the 20th and 21st centuries they fought — fiercely — to preserve their culture, language, and traditions.

The Berbers, The Original Inhabitants Of The Maghreb

W. Robrecht/Wikimedia CommonsBerber cave art. Berbers have inhabited the Maghreb region since the beginning of recorded human history.

The history of the Berbers goes back more than 20,000 years, to a time when the Sahara Desert was lush and green. They left behind cave drawings and rock art, and appear in early Roman, Greek, Phoenician, and Egyptian texts. The very term “berber” might come from the Latin “barbarus,” which was used to refer to non-Latin speaking peoples.

Some Berbers now prefer to be called “Imazighen” or “free men,” but they’ve always been made up of disparate tribes, including the Mauri, the Kabyle, and the Chaouis. Some of these Berber tribes established kingdoms in antiquity, and some of these kingdoms — including Numidia and Mauritania — were incorporated into the Roman Empire in the second century B.C.E.

Though Berbers absorbed some of the culture from the empires they encountered, the greatest influence on Berber life would be the Arabs. In the seventh and eighth centuries, the Arab Conquest brought a new language (Arabic) and religion (Islam) to the Maghreb. The conquest also drove many Berber tribes into the mountains like the Kabylia, the Aurès and the Atlas Mountains, as Arab forces established strongholds in the plains and deserts.

There, in regional isolation, many Berbers were able to preserve their language and culture even in the face of growing Arabic dominance. They managed to hold on to a distinctive and simple way of life — one that made them one of the most unique people in history.

Luc Viatour/Wikimedia CommonsA Berber Village in Morocco’s high Atlas Imlil valley.

Indeed, their lifestyle is based on traditions that go back tens of thousands of years. And as the 20th century approached, many Berbers maintained their way of life even in the face of increasinging modernity.

Inside The Berber Way Of Life

Tucked into enclaves across North Africa, Berber societies developed in places like the mountains of Kabylie in Algeria, the Atlas mountains in Morocco, and the Ahaggar mountains in the Sahara Desert. Today most Berbers live in Morocco (where they make up 40 percent of the population) followed by Algeria (where they make up roughly 20 percent of the population). Berber communities can also be found in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mauritania, Niger, Mali, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and even abroad.

Some of these Berbers lived a nomadic life — where camels play an especially important role — but others established farms and subsisted off crops like wheat, dates, and olive oil. Many Berbers live in communities where women see to the day-to-day needs of the home, and men take care of livestock, often migrating with their flocks during the year. Berbers in places like Morocco are especially known for their skill craftsman skills, and make things jewelry, pottery, and henna art.

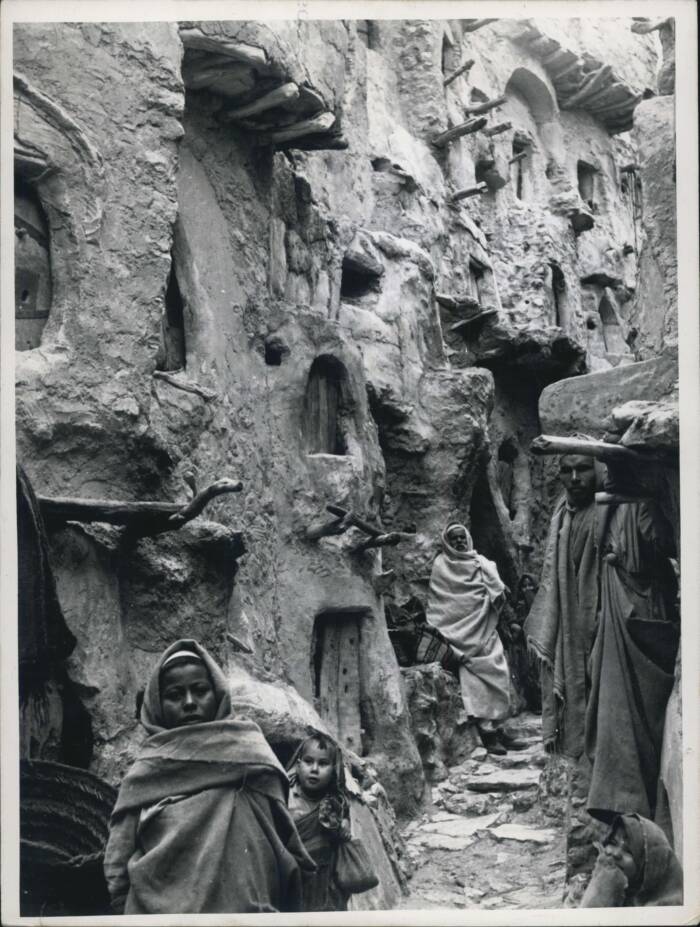

Keystone Press / Alamy Stock PhotoA centuries-old Berber fortress in The Jebel mountain range, where Berbers stored their harvests of wheat, dates, and, olive oil. Circa 1950.

Sometimes Berbers live in tents, sometimes in caves, and sometimes in houses made of stone or clay. Berbers often dress in Arab style, with turbans for the men and headscarves for the women, but the Tuareg people of the Sahara — who live across Libya, Algeria, Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso — are known for their indigo blue robes (daraa or boubou).

Hanay/Wikimedia CommonsA Tuareg man in Morocco. 2008.

As for religion, most Berbers are Muslim — and have been since the Arab Conquest centuries ago (though a minority of Berbers are Christian, including the Kabyle people of Algeria). This goes to show the Berbers have adapted to other cultures over time, an adaptation that continues to this day. Indeed, many modern-day Berbers have left their traditional homes to work in urban centers, which in turn has brought modern ideas and technologies from Arab and European capitals back to Berber communities.

But despite this cultural exchange, there are still tensions between Berbers and their majority Arab countrymen across the Maghreb.

Surviving Persecution And Modern Life

National Museum of World Cultures/Wikimedia CommonsBerber women in the 1970s. Though Berbers have kept many of their traditions alive, they’ve also faced challenges of modernity and political suppression.

It wasn’t until the Arab Conquest — and later French colonization — that the Berbers were seem as a cohesive group. For centuries they had belonged to disparate tribes and spoken different languages. But in the 20th century Berbers began to identify as Berbers — or rather, as Amazigh, or free men. This push to develop a cohesive identity, however, led to pushback from political forces seeking to suppress their languages, culture, and history.

As countries across the Maghreb achieved independence from France, some saw the Berbers — and the emergence of Berber nationalism and pride — as a hindrance to establishing a national identity. In response, many countries with large Berber populations cracked down on them. Algeria and Morocco both suppressed or outright canceled Berber studies program, and the cancellation of a lecture on Berber poetry in Algeria triggered protests in the 1980s. In 2001, protests broke out again in Algeria after a young Kabyle man named Massinissa Guermah died while in police custody.

In Libya, which has a much smaller Berber population (roughly 5 percent) the government took an especially harsh stance. Because the Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi believed in building a cohesive Arab nationality, Berbers faced draconian punishments for attempting to preserve their culture. Any attempt to promote Berber identity — from speaking their language, to publishing books in their language, to flying the Amazigh flag — would result in severe consequences, or death.

And even after Gaddafi’s fall in 2011, Berber inclusion in Libyan society wasn’t assured.

Imago / Alamy Stock PhotoBerbers carrying both the Libyan flag (in the forefront) and the Amazigh flag (in the background) in 2011. Berbers were treated severely under Muammar Gaddafi but have had to push for their rights even since he was disposed.

“Our problem is not only the 42 years of the former regime,” Mazigh Buzakhara, a Libyan-Berber activist, told CNN in 2012 after Gaddafi’s fall. “Our problem is 1,400 years of Arab or Islamist mentality that has been brought to North Africa itself. It’s a mentality problem, not only with the common people but in the heads of the politicians.”

Elsewhere, Berbers have had some more success. The Tamazight language is studied in Algeria (though it’s not recognized as an “official” language) and Moroccan Berbers succeeded in establishing the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (today called the National Council for Amazigh Languages and Culture) in 2001. There, Tamazight is recognized as one of the country’s two official languages alongside Arabic.

But the story of the Berbers is far from over. It’s a tale that started tens of thousands of years ago, when Berber tribes roamed the lush Sahara, developed their culture, and clashed with emissaries from Rome, Greece, and other empires. It’s a story that continued throughout the Arab Conquest of the seventh and eighth centuries, and marched straight into modern times where Berbers — though no longer living exclusively in the mountains — have maintained a hold on their culture and traditions.

Koukoumani/Wikimedia CommonsA crowd of young Berbers celebrating the Amazigh New Year in Algeria. Though many countries have tried to suppress Berber traditions, Berbers have fought back for the right to speak their language and practice their culture.

And today, the story is still being told. Berbers — Amazigh — are a more cohesive group than ever. Though spread across different countries in Africa, they continue to fight for their right to exist, to speak their language, and to celebrate their culture. Though this struggle isn’t always easy, the Berbers have faced towering challenges before. They survived as the Sahara turned to desert, as empires crumbled, and as new religions and ideas came to their borders. Surely, they’ll survive whatever comes next.