Mildred Harnack moved to Berlin with her German-born husband in 1929 and joined a Nazi resistance group — and was later sentenced to death by Adolf Hitler himself.

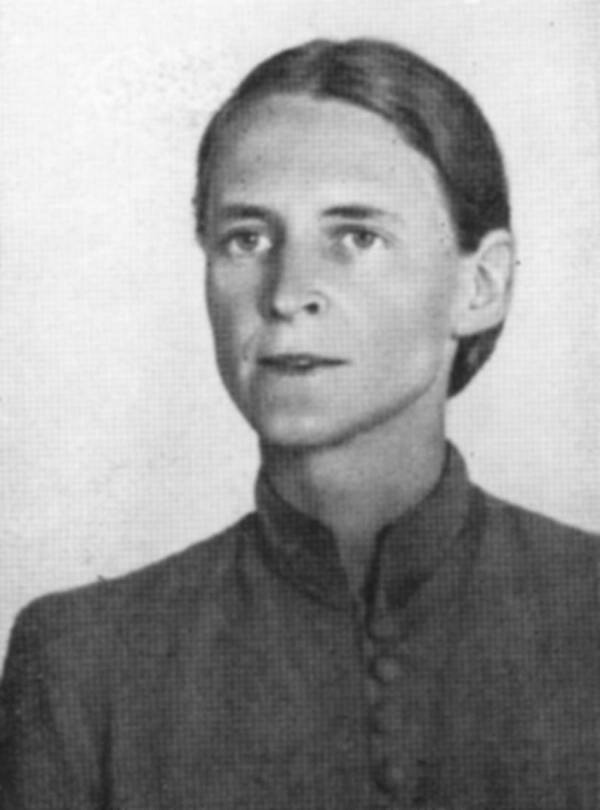

Wikimedia CommonsMildred Harnack’s mugshot, taken in 1942.

“Despite our being separated, let’s not be worried and anxious,” Mildred Harnack wrote to her family back home in Wisconsin in August 1942.

But her family had reason to worry – war raged in Europe, and Harnack had moved to Berlin over a decade earlier. And although she could not admit it in writing, she had joined a spy network to undermine Hitler and the Nazis.

It was the last letter Harnack’s family would receive. Within months, the Gestapo captured Harnack and put her on trial. And Hitler himself made sure Harnack received a death sentence.

An American Teacher’s Path To Germany

Mildred Harnack was born Mildred Elizabeth Fish on September 16, 1902, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. According to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she grew up learning both English and German due to the high German population in her neighborhood.

Harnack dreamed of becoming a writer, and she earned a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in English literature. In 1926, while teaching at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she met Arvid Harnack, reportedly when he took a wrong turn in a university building and accidentally ended up in her class.

Arvid Harnack was a German lawyer and a Rockefeller Fellow who was studying in the United States. In her book Resisting Hitler: Mildred Harnack and the Red Orchestra, Shareen Blair Brysac writes, “He went up and introduced himself. He apologized for his faltering English, and she apologized that she didn’t speak German very well. And he proposed he study English with her and she study German with him. And that was the beginning of the romance.”

The two shared an instant attraction. In her memoirs, Inge Harnack recalled the letter her brother sent home to Germany. “I still remember how a letter arrived for my mother with the laconic sentence, ‘I’ve met a girl with the beautiful name, Mildred.’”

Within months of the first letter, Arvid Harnack wrote again. “I am very happy. I’ve got engaged,” he related. “I made up my mind when I saw her for the second time.”

Arvid and Mildred Harnack married just a month later, on Aug. 7, 1926.

Arvid Harnack soon had to move back to Germany after his fellowship ended. After several years of living apart, Mildred Harnack joined him in 1929. By 1931, Harnack had enrolled at the University of Berlin to earn her doctorate while teaching classes on American literature. Her husband took a job with the German government in the Ministry of Economics.

The German Resistance MuseumArvid and Mildred Harnack in Jena, Germany in 1929.

The rise of Hitler would destroy Mildred Harnack’s academic career. Only fifteen months into lecturing at the university, she was fired for not being “Nazi enough.”

Harnack had been open about her criticism of the Nazis. According to the Los Angeles Times, she wrote of the Nazi Party in 1930, “It thinks itself highly moral and like the Ku Klux Klan makes a campaign of hatred against the Jews.”

Mildred Harnack soon decided to do everything she could to take down the Nazi regime.

Mildred Harnack’s Role In The Red Orchestra And Her Eventual Arrest

In 1933, after Mildred Harnack was fired from the University of Berlin, she and her husband joined a small resistance group working to undermine the Nazis from inside Germany. The Gestapo called them the “Red Orchestra” because they transmitted information to the Soviet Union via radio “concerts.”

Members of the Red Orchestra distributed anti-Hitler pamphlets, kept records of Nazi violence, and later passed German economic and military intelligence to the Soviet government and the Allies. And Harnack became a key recruiter for the underground organization thanks to her position teaching night school in Berlin.

When Harnack’s students expressed discontent with the Nazis, she connected them with the Red Orchestra. In the mid-1930s, she took a position as a literary scout for a German publisher, which allowed her to travel across Europe meeting with other members of the resistance.

Eventually, however, the Gestapo discovered one of the Red Orchestra’s radio transmissions and began arresting its members. The Harnacks were captured in Nazi-occupied Lithuania in September 1942 as they attempted to flee to Sweden.

The Gestapo threw Mildred Harnack into Charlottenburg Women’s Prison. Every day, a Nazi interrogator tried to break her. And in December 1942, she faced trial for high treason.

That same month, her husband was executed. Arvid Harnack was hanged with a foot-long rope, a method Nazis used to prolong their victims’ agony. Before he died, he wrote one last letter to his wife. “You are in my heart… My greatest wish is that you are happy when you think of me. I am when I think of you.”

During her own trial, a panel of judges sentenced Mildred Harnack to six years of forced labor at a prison camp.

According to the New York Times, as Harnack awaited her punishment, the Nazis instead transported her to Plötzensee Prison in Berlin. Adolf Hitler, unsatisfied with the spy’s prison camp sentence, had overruled the judges. Harnack would face execution like her husband.

The Execution Of Mildred Harnack And Her Legacy Of Bravery

On Feb. 16, 1943, the Nazis beheaded 40-year-old Mildred Harnack by guillotine. They noted it took her seven seconds to die.

She had lost her life resisting the Nazis. But few people today know her story.

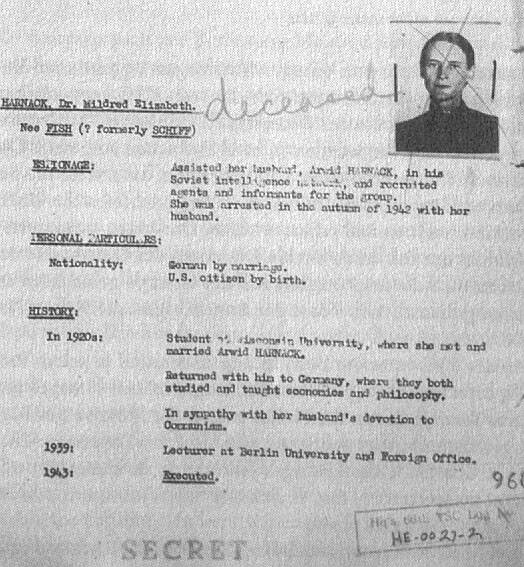

After the war, the War Crimes Group of the U.S. Army investigated the execution of the Harnacks. “While Mildred Harnack’s actions are laudable,” reported a top-secret memo, “she was plotting against the German government, was given a trial and there appears to be sufficient justification for imposition of the death sentence.”

The U.S. Army soon closed its investigation into the Harnacks. They had given intelligence to the Soviets, and in the new Cold War climate, that was enough to condemn them.

Even worse, captured Nazis trying to avoid the Nuremberg Trials claimed the Red Orchestra was a communist spy ring still operating in the U.S. The lie helped bury Mildred Harnack’s heroism.

National ArchivesThe U.S. Army file on Mildred Harnack created c. 1947.

Members of the Harnack and Fish families fought for decades to clear the names of Arvid and Mildred Harnack. Only after the Cold War ended did their efforts succeed.

Today, Mildred Harnack is seen as a World War II hero. Rather than use her American passport to flee Nazi Germany, she remained to fight against injustice. When Harnack’s family had urged her to return to the U.S., she’d replied, “Well it’s not a question of how dangerous it is, I’ve got work to do.” She became the only American woman ever put to death on the direct order of Adolf Hitler.

And when she was facing that certain death, Mildred Harnack’s final words were: “And I have loved Germany so much.”